•Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan on release of his biography,1992. Statement was included in the book

Monthly Archives: September 2012

The Voice From Heaven

Known as a “Singing Bouddha” in Japan, the “Quintessence of human singing” in Tunisia, the “Voice of Heaven” in the United States and the “Pavarotti of the Orient” in France… Pakistan’s most revered Qawwal singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, made the whole world resonate to the lyrical heights of Qawwali, a secular form of Sufi song that calls to divine ecstasy. His nearly superhuman vocal abilities, extraordinary improvisational skills, troubling intensity and softness of his voice, his kindled presence on stage, his many encounters and colorful musical cross-blendings and the enduring love that millions of fans lavished upon him worldwide all helped him bring the mystical music of Sufi’s to international stage becoming one the most celebrated superstars of World Music. He simply kicked his audience into a state of trance and ecstasy , he made them cry and weep at will, he made them dance and sing along although most of foreign audience never understood a word he uttered. He brought Qawwali music from mosques and shrines of Sufi saints to the common man’s winning the applause of the most diverse audiences ever while keeping faithful to his message:

When I’m sin-ging, the distance between God and me becomes lesser”, he said. “This music brings people together”.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was a living legend and a bridge between tradition and modernity,Orient and Occident, the sacred and the profane. Since his untimely death in 1997, his legacy has continued to spread among major artists .

This blog is not a tribute , its a journey of my life ( and may be yours) form now and forever exploring the great messenger whose voice made me feel the existence of God. This project is intended to feature all the untouched aspects of the Legend, and will act as a guide to get maximum from legacy to achieve the utmost peace and ecstasy.

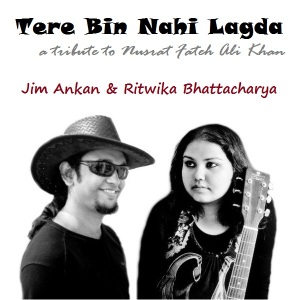

Tere Bin Nahi Lagda ….. A tribute to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

Tere Bin Nahi Lagda with a jazz essence released online by Jim Ankan and Ritwika Bhattacharya

There aren’t enough words to surmise Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s contribution to the world of Sufi music nor his limitless musical genius. There’s certainly no way to replicate his six-octave vocal range or his meticulous compositions. “Tere Bin Nahi Ladga”, recently covered by Rittwika Bhattacharya and Jim Ankan Deka, is an interesting rendition of the virtuoso’s soulful melody.

Mouthpiece For The Divine

Originally Authored By:

“I do not sing to become famous or wealthy. All praise is to God that I lack nothing. But, when I sing, it’s because I inherited this talent from my great heritage. I thank our ancestors many times, I only want to impart the message that they themselves imparted and be of service to you in making you aware of this message.”

—Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, 1948-1997

On August 16, 1997, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan died and the world lost one of the most dynamic singers of the century. For six centuries, Nusrat’s family have performed qawwali music at royal courts and Sufi centres. Nusrat’s father insisted that he become a physician. But after mastering the tabla at the age of 16 and visualizing dreams of himself performing at the famous Khwaja Mo’in ud-din Chishti’s shrine in Ajmer, India, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan began a 33 year journey as the ‘mouthpiece for the divine’.

At the old Mehfil-e-Sama grounds in front of Data Darbar in Lahore (now covered with ugly concrete as part of the new Data Darbar complex), we used to go to the all-night qawwali sessions during the annual Urs. It was there in 1972 that I heard Nusrat for the first time, a year after his father’s death and was amazed by the virtuosity of this round young man. The energy, the passion, pushing the music to its limits with eyes squeezed shut, everything, the world would one day know him by, were already there. An enthusiastic Lahori crowd roared its approval, galvanizing the young qawwal to even more high-pitched and painfully powerful creations.

A couple of years later, as a homesick student in Germany during the 1970s, cassettes of Nusrat from the Rehmat Grammophone House in Faisalabad were all I asked for from home. It was Nusrat’s music that during those long years filled my little room with a power and freedom that made me proud of my identity. I still remember sophisticated Pakistanis turning up their noses at his music and saying, “Adam, do we really have to have this cacophony on so loud?” Yet they were the same ones, who ten years later used to ask me superciliously, “I’m sure you haven’t heard Nusrat’s latest. Isn’t he great?”