Of course, I snapped at the chance, and then I asked my boss if I could review the show. He shrugged and referred me to the entertainment editor. I made my pitch: Nusrat’s a breakthrough artist rising on the global stage, endorsed by Peter Gabriel, who had released two albums by him on his Real World label, I said. The editor was unmoved. Nusrat’s the most popular, beloved singer throughout Pakistan and much of India, I added.

My editor laughed. Snorted even. Dismissively and derisively.

Reluctantly, and still smirking, he agreed to give me a paltry 300 words in the coming Monday’s paper. That, I figured, was about one word for each, oh, million or so of Nusrat’s fans.

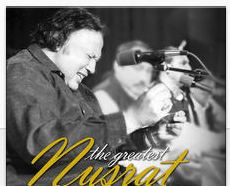

So as we note the Aug. 16 ten-year anniversary of Nusrat’s death in London at age 48 — twenty years to the day after Elvis Presley died, and make of that coincidence what you will — let’s take the opportunity to laugh right back at that editor, derisively and dismissively. Frankly, we probably could have started that retort not long after his patronizing response to my pitch, as Nusrat was soon to become one of the most familiar non-Western artists on the global stage.

By the time he died of complications from diabetes, he was an international icon, celebrated by figures from Eddie Vedder (who collaborated with him on a track for the ‘Dead Man Walking’ soundtrack) to Jeff Buckley (who went so far as to learn Urdu pronunciation in order to perform a Nusrat piece) to superproducer Rick Rubin, who was even talking about putting the qawwali giant in the studio together with Johnny Cash. By the mid-’90s, he was being promoted by the William Morris Agency, and a star no less than Madonna led a cadre of the beautiful people in attending a Los Angeles concert. Compact discs of the singer’s recordings piled up: official releases from Real World, imports or bootlegs from Pakistani collections, concert recordings, remix projects galore (a few authorized, many more not). All Music Guide’s certainly incomplete discography lists 66 titles released from 1988 on, plus more than three dozen anthologies. (See below for a brief buyer’s guide.) “Nusrat” became a brand, a one-name identifier. Like, well, Elvis. Or Madonna. Pretty amazing, considering that he sang extended, sinuous Sufi songs of desire and devotion — in Urdu.

As it turned out, it didn’t matter how many words I had, or in what language, for that matter, to write up that 1990 event. I don’t think I had the facility to describe what I saw and heard. Probably still don’t. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan & Party (the generic term for Pakistani ensembles) sat cross-legged on a low stage at one end of the room and — after a little warm-up consisting of a bit of squeezed harmonium, tabla and vocal stretching — launched into pealing, melismatic lines, calls-and-responses with the other singers, physically illustrated with snaky hand gestures from the ample Nusrat, who had entered what appeared to be a trance. The South Asians not only hung on to but anticipated every note, cheering and keening as the vocals twisted to heights of intensity, fans sometimes parading to the front of the stage to present currency of various denominations, some for the cause, some for the musicians themselves. I have no idea how long the show went on.

I don’t recall what I wrote exactly, but I remember scrambling for comparisons. Attending Nigerian ju-ju music titan King Sunny Ade’s early ’80s L.A. debut was the only remotely relatable revelation I’d had before. For Nusrat I stretched for reference points that might mean something to readers — American gospel, John Coltrane’s ‘A Love Supreme,’ Miles Davis, probably Ravi Shankar; none of them were adequate either individually or collectively. I do know that my editor (not the same one) took out all of those mentions except the gospel one, which left the impression very narrow. Regardless, I’d probably be embarrassed to read what I wrote then for how naive and uninformed it was. But at least we got something in. And I was hardly the only one who was uninformed.

The Hilton show stands at a turning point in the Nusrat legacy. All of his previous U.S. appearances had been house concerts and benefits with no awareness outside his community. But then his profile started to rise — this was the last time he’d be appearing in such a modest setting here. “What he did for world music, first of all, was make it so all the people playing houses can do concerts,” says Baba Ji, a Pakistani-born producer and promoter who worked closely with Nusrat in America. “It’s like Bob Marley, though he sang in English. Nusrat came from Pakistan, a little village, and sang in Urdu. The thing was, when you went to his concerts, no matter what color you were or language you spoke, within 30 seconds you were connected.”

But a decade after his death, Nusrat remains pretty much the only qawwali singer known widely outside the Sufi world, even more ahead of the rest of a large pack than, say, Marley in the reggae realm. In fact, the only other ones with much international profile have been relatives of his, in particular his nephew and protégé Rahat Nusrat Ali Khan (who will headline a tribute to his uncle Oct. 14 at London’s Royal Festival Hall) and a cousin, Badar Ali Khan, who himself passed away in March at only 39.

“The thing I pick up from people is somehow there was something universally accessible and emotionally involving that he had,” says Michael Brook, who will also be part of the London concert. “He certainly was very, very good at what he did, but there was something more than that. I quite honestly am puzzled. Not that I don’t think he was great. But there was a mysterious universality that I don’t think was just musicianship. I don’t know what it was, but it certainly reached a great number of people.”

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: A Buyer’s Guide

Real World’s 1988 set ‘Shahen-Shah’ provided the first nudge into “mainstream” consciousness for Nusrat, and it still might make for the best introduction. The tracks are mid-length (mostly around seven minutes or so) and to the point, the sound clear and crisp, and the performances all bear an immediacy. Further Real World releases expand their scope and bring fans further into the qawwali world, with the Michael Brook-produced ‘Shahbaaz’ (1990) and the slightly more unconventional ‘Devotional Songs’ (recorded in 1988 but released in 1992) and ‘Love Songs’ (a set of romantic ghazals from the same sessions) giving a full sense of Nusrat’s blend of classical and folk, spiritual and secular. The ‘Devotional Songs’ opener, ‘Allah Hoo Allah Hoo,’ might be as close to a Nusrat signature piece as there is. A five-disc ‘In Concert in Paris’ series from French label Ocora gives a fuller sense of the extended live experience — the set’s five hours document just two performances, from 1985 and 1988. ‘The Final Studio Recordings’ collects the work Nusrat had been doing with Rick Rubin before his death and also is a solid starting point. As well, ‘The Voice of the Century,’ a set produced by Baba Ji in 1995, will see its first release this fall and is a strong complement to the other highlights.

When it comes to the untraditional and remix projects, step carefully. The two Brooks-produced albums, 1990’s ‘Mustt Mustt’ and 1996’s ‘Night Song,’ stand far above the rest and work entirely on their own terms. The former features subtle, sympathetic settings crafted by the producer for pre-existing Nusrat vocal tracks. The second, though, is a true collaboration, Nusrat and Brook each reaching to the other, artistically speaking, finding not just common ground but exploring new territory for both participants. An early remix album, ‘Magic Touch,’ features Nusrat tracks rejiggered into dance music by Anglo-Indian DJ Bally Sagoo, succeeding much better than nearly everything else of its kind, the others generally suffering from the common remix malady, with the productions being more about the remixers’ sensibilities than the source’s.

by Steve Hochman, Spinner